Saint George and the Dragon: the origins of the legend

In our imagination George, the knight-martyr, is the saint that kills the dragon, but his most ancient representations tell us a completely different story.

As a symbol of evil and paganism, the dragon appears frequently in the stories about medieval saints. The list of dragon slayers saints is definitely very long: Theodore, Sylvester, Margaret and Martha (that however just tamed the monster) are just the most famous ones. Beside them, St. Michael Archangel led the battle against this emissary of the Apocalypse.

Nevertheless, none among all dragon slayers became object of the same popular veneration as St. George did, chosen as patron saint of England, Portugal and many other countries.

We just know about him that he was a Cappadocian soldier martyred under Diocletian, but we lack any other historical element about his life. Therefore, all stories about him are the result of medieval additions that enriched the original pattern during centuries.

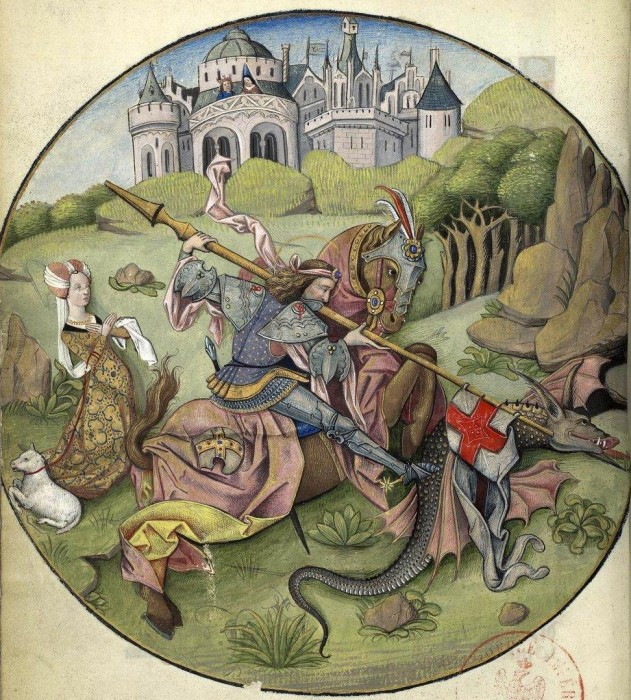

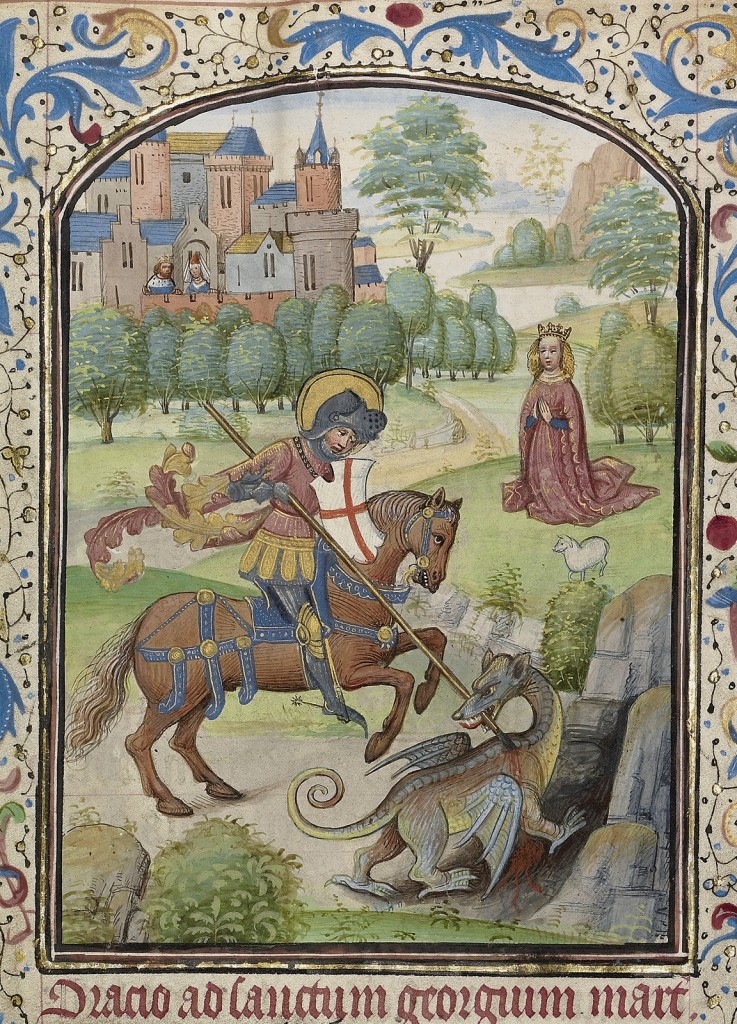

The traditional iconography of George is based on his most famous miracle – the killing of the dragon. As narrated in the Golden Legend by Jacobus de Voragine (also known as Legenda Aurea by Jacopo da Varagine), the event is well-known: Selem is besieged by a horrible monster and, to keep it away from the Libyan town, the citizens drew lots to decide whom among the youngest in town to sacrifice to the monster. As the daughter of the king has to be sacrificed, St. George appears riding his horse and he manages to neutralise the dragon (the scene immortalized by artists). He then invites the princess to rope the dragon, now domesticated, to lead it into the town: witnessing this prodigious event, the king and the whole population converted to Christianity and, at the end, the dragon is killed.

Starting from the 12th century, the image of the fight against the satanic creature becomes more and more widespread all around Europe, as it is shown in painting…

…in sculpture…

…and in illumination.

In the Western culture the iconography of this saint is based mainly on this episode and other miracles and his martyr are seldom represented: the dragon becomes his characteristic feature.

However he has not always been represented according to this model: on the contrary, at the beginning of his cult there was no dragon in his stories, not to mention his representations.

The most ancient representation of St. George dates back to the first half of 10th century and can be found in Armenia, in the church of the Holy Cross built on the isle of Akdamar. Here a bas-relief shows three saints riding and, among them, George can be identified, represented as he spears not a dragon, but an anthropomorphous figure. The other two knights are St. Sergius killing a fierce animal (in the middle) and St. Theodore who definitely does fight against a dragon (on the left).

In Georgia, on the cathedral of Nikortsminda (beginning of the 11th century), the same scene can be seen: on the left Theodore kills a dragon-snake, while on the right George hits a human figure.

Actually at that time the dragon slaughter saint par excellence was Theodore of Amasea, a knight saint known from the 7th century for having defeated the monster. For this reason in the Early Middle Ages dragons were associated only to this saint. In the successive centuries artists will continue to represent St. Theodore together with the dragon (as in the statue over the column in Piazzetta San Marco in Venice), but this iconography will become less and less common.

Until the 11th century in no story about St. George the killing of a dragon was ever mentioned: he was venerated simply as a soldier-martyr that converted infidel peoples. For this reason the traditional image that had represented him until this moment was that of a knight spearing a man, symbol of the pagan persecutor and of heresy.

Right in this moment the legend on the fact that Giorgio too faced a monster rose in Eastern culture, maybe based on those very illustrations.

As a matter of fact, in frescoes and in bas-reliefs the saint was always represented together with Theodore who was fighting against his own dragon: for this closeness artists ended up by associating both saints to the monster, up to the point that George was completely “assimilated” to the artistic theme of the dragon. The first proof of this evolution is in Cappadocia, in the church of St. Barbara in Soganli (11th century).

In the meantime, around the image of St. George killing the dragon a whole story started to be developed: the more the saint was venerated, the more the story was enriched with details.

The first texts related to the episode date back to the 11th century and include already all elements that we know: the lake monster, the princess saved from its jaws, the domestication of the dragon led to town, the conversion of its citizens.

The story of St. George and the dragon was spreading over, but it would have remained linked to eastern regions for a long time, if Crusades would not have taken place. Christians easily identified with a triumphant saint that had liberated the region from infidels: as patron saint of Crusaders, no one was more appropriate than George.

But the saint could have been so successful among pilgrim soldiers for another element: they saw in Byzantium a large painting showing a sovereign spearing a dragon, treading on it. This image was in front of the vestibule of the Imperial Palace and represented Emperor Constantine triumphant over the “tyranny of the ungodly”, the symbol of which was a dragon-snake. This image was very popular in ancient times and it is possible that Crusaders had seen a copy of it, later superimposed onto the symbol of the dragon slayer saint.

In a very very quick time the cult of St. George spread all over Europe as simultaneously did the representation of the knight killing the dragon – in England the first image of this kind dates back to the beginning of the 12th century. Whereas in the Eastern regions the monster looked more like a snake, its version brought by the Crusaders to the Western lands grew in dimensions and it acquired paws and wings, becoming the dragon we all know.

Folia Magazine wishes all of you the happiest of Holidays with this delicate,…

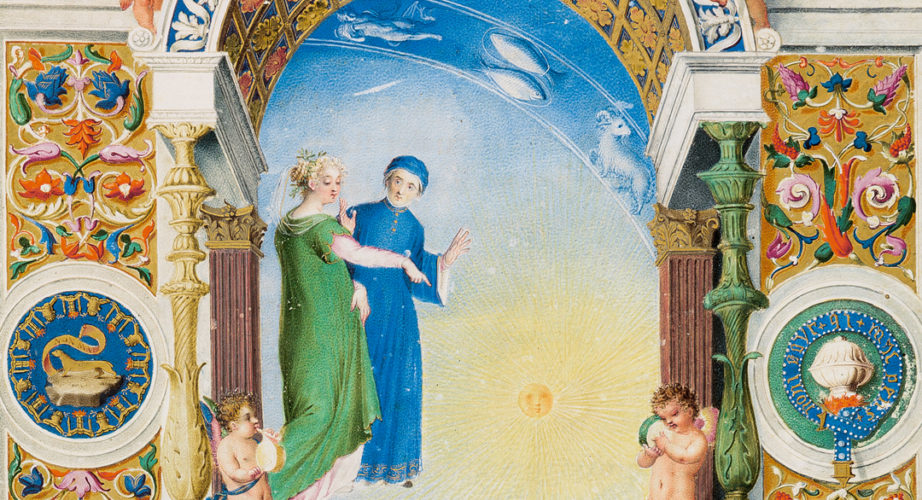

The cover page of the Paradiso displays an architectural structure that is complex…

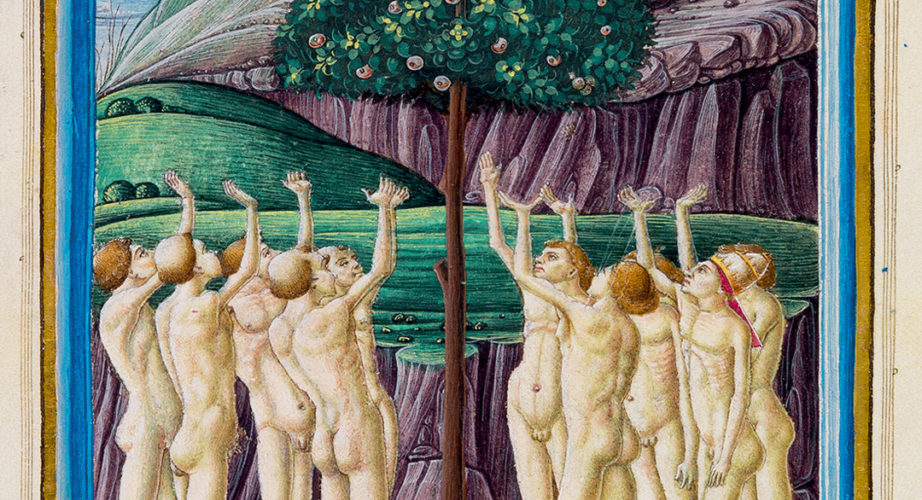

As the three poets continue their journey through Purgatory, they reach the sixth…